Few things dig into your soul like looking out across a classroom of completely disinterested faces who might be variably looking at their computers or phones. It is easy to get a bit annoyed or even resentful at this point, wondering what is wrong with them for not being engaged in what you are saying and doing. Afterall, as an educator you are teaching stuff that you (hopefully) believe is important. You would are interested in the material, and they are not, you start to wonder “why don’t ‘they’ get it?”

One problem lies in that very formulation of the problem being with “they” rather than with “it.”

The “it” here I am referring to is the material that is the delivery mechanism for academic content, whether it be a PowerPoint deck, journal article, textbook, conference presentation, or some other thing that is meant to convey and clarify but might just confound and confuse. Not only do we as professors “profess”, but more importantly we transmit. We communicate complex information to an audience with the intent of them being able to understand and internalize it (or at least meet assurance of learning standards). When the methods of transmissions fail, it is nearly impossible to meet the goal of educating.

You really can’t blame instructors for this potential failure to communicate with the tools that they have been given and the methods they have been taught to use. Looking back on my own educational experiences, the methods used were pretty traditional. For all of the claims of higher education being liberal bastions, the place really has changed much for hundreds of years. The technology has changed, but the process remains mostly the same. A person is at the front of a group, speaking on some topic over which they have proclaimed expertise, and the audience is expected to be recipients of that content in the form in which it is delivered.

As an academic, you spend a lot of time turning your work into content for other academics. It makes sense that this is the approach you would take since that is the universe that you are in. Good work is defined by those who share in that work, which not surprisingly are other academics. When you go to an academic conference to present, submit an academic journal article, write a book for an academic press, you are doing so for other academics.

Given this is the landscape, how can we expect academics to do any different when going into the classroom? It is what we know, so that is what we do.

Further complicating things is that when becoming a professor there was an astonishing lack of classroom preparation. My informal conversations with others in university education reveals a similar pattern. We were tossed into the classroom and had to figure it out. As with most professions, you learn by watching others do the job, imagining that this is how the job should be done.

In retrospect, it might have been a good thing because what would the outcome have been if I had training from other academics? It would likely have been duplication of academia, which was already accomplished through my immersion in years of education.

This is not to say that mentoring or training programs in education are not helpful or useful. However, it is to say that in order to learn how to engage audiences with academic material, we need to cast our attention beyond academia and into areas that have already figured out engagement. We need to learn from different approaches from those that have been able to create engagement in their materials.

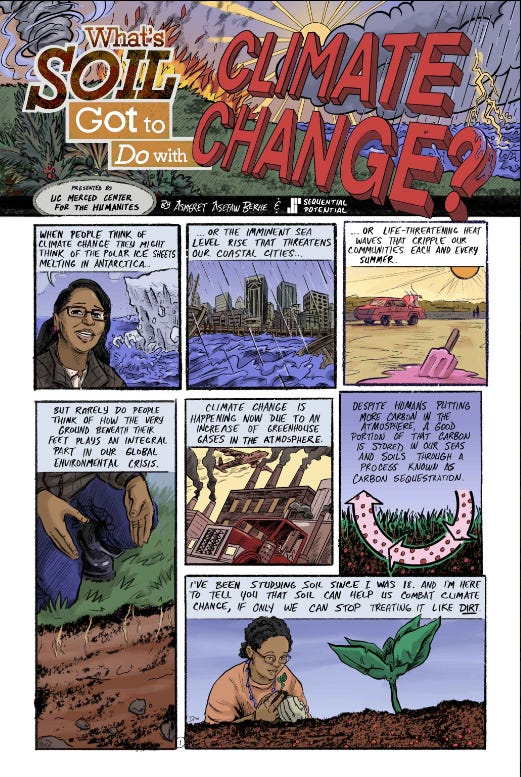

Enter the folks from Sequential Potential who have made it their mission to turn academic content into comic books and graphic novels. The effort came from the confluence (in the form of the marriage) of Darick and Emily Ritter. Darick is an artist and Emily is a Professor of Political Science. Emily knows the way of the academics, including their customs, language, and rituals. Darick knows how to illustrate and depict in visual forms. It made a lot of sense to combine their worlds, kind of like chocolate and peanut butter. They are great in their own right, but together everything gets elevated and magical things happen.

Thus was born Sequential Potential. Why can’t we take academic material and render it in a form that is stripped down and more engaging? Their answer was, we can, and we should.

As a sociologist, I have long marveled at what I call sociology’s self-imposed irrelevance. By this I mean only talking in ways that each other can understand and then wondering why no one listens to us. If I am speaking in a language that you can’t understand, then I can’t blame you for not listening. If I am speaking in the only language I know, then you can’t blame me for not being able to communicate differently. The key then is to learn a different language.

That of course takes time and a lot of effort. I could learn another language, or I could work with a translator. Sequential Potential becomes that translator, helping academics transform what they know how to say into content that others can understand.

In Episode 83 of Experience by Design, we discuss their projects and work with Emily and Travis Hill. Travis is a doctoral candidate in history and a long-time comic nerd and comic creator. Beyond exploring what they have done so far, we discuss the larger issue of translating scholarly material for a broader public. As academics, if we want our work to matter, we have to put it out there in a way that others can understand. We have to value that kind of content and the contributions that it can make. We have to measure impact beyond citation indices and into public awareness and use. And we discuss if we can’t do that on our own as academics, then we need to work with people like Sequential Potential to get the help we need.

As a result, we might just change those disengaged faces in the classroom into ones that are drawn in by the frames of a comic strip.